With the arrival Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps on Friday, director Oliver Stone offers us another critique of the cutthroat world of finance, and the soul-selling that often goes along with it. It is with this in mind that I have compiled a list of the best movies that I believe most successfully comment on the events of our society, be it today or 50 years ago. Some of these films had to the power to prompt congressional action or be the catalyst for an important legal decision. Others are notable not necessarily for the social issues they contain, but for the social climate they were created in. For the purposes of this article, we shall broaden the definition of political/social issue films to include these additional attributes.

10. The Michael Moore Filmography

Regardless of what you think of Mr. Moore (fat, commie pig, or freedom fighter for the working class) and his antics, his films are always interesting. I usually find myself not in agreement with his position as a matter of fact, but afterwards I always find myself touched by the humanity of the everyday people on screen enough to brush up on my knowledge of the topic at hand, be it universal healthcare or “evil” corporations and further define my own opinion. I concede that Moore’s films are one-sided. That’s his right. It’s his film. No landmark decisions have been made as a result of his movies, but each one at the very least provokes discussion and sheds light on the important issues of our times, on a consistent basis. To do this while making a film full of heart and entertainment is no small feat.

9. The Public Enemy (1931)

James Cagney’s starmaking vehicle is a prime example of all the pictures made during its time by filmmakers who had to tell their story within the confines of the Hays Code, a censorship model that explicitly dictated what content could not exist within a Hollywood film. The law could not be defeated, no criminal glorification, no interracial relationships, no drug use, etc. Until the code was abandoned in favor of the modern rating system in 1968, films had to abide by it if they wanted distribution. However, certain filmmakers, among them William Wellman, director of Public Enemy, found certain loopholes that allowed them to tell get away with certain things. James Cagney’s gangster role of Tom Powers is a glorified figure, and after the Code began to be actively enforced in 1934, Wellman, rather than recut his film, simply added a half-hearted title card at the beginning stating that Tom Powers was a rapscallion and not to be admired to satisfy the requirement. The film is noteworthy both as a scintillating entertainment and as an example of a product designed to fight censorship and the artistic hindrances of the time.

8. Natural Born Killers (1994)

Critics have been divided over Oliver Stone’s take on America’s celebritization of violence and killers since it was released 16 years ago. Some believe it’s a vicious, over-the-top satire that successfully lambasts violence in media, others believe the film becomes what it’s supposedly criticizing, with Stone’s point getting lost in the excessive carnage depicted on screen. The movie supposedly inspired several copycat killings after his release, and as it turns out, a friend of John

Grisham was a victim, prompting him to support the lawsuit of Patsy Byers, which argued that Stone and Warner Brothers should be held responsible for the murders because they “released a film they should have known would have incited violence.” A guilty verdict would’ve had widespread effect on the film industry and content of movies, but the court eventually ruled that Stone was protected by the 1st Amendment and the case was dismissed. The argument over whether real life violence is caused by entertainment and media continues.

7./6. Robocop/Wall Street (1987)

A cursory glance at either of these two titles suggests that they don’t belong together, but they actually share very similar criticisms of the corporate greed of the 1980s. In Robocop, the main villain is the vice president of the Omni Consumer Products (OCP) corporation, a company whose eventual goal is to take over and privatize the entire city of Detroit. The film is most successful in its critique via the commercials that air between news broadcasts.

Wall Street marks the rise and fall of one Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), the son of a working class father who wants to leave the low proving grounds of the Jackson Steinham firm and be a player. The only way that he can accomplish that is by impressing Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas). Eventually Gecko takes him under his wing, and shows him excess like he’s never even dreamed, regaling him with all sorts of perks and speeches of how “greed is good.” Sure, he’s the bad guy, but Gecko’s allure is further defined in an old interview with Michael Douglas on the DVD, where he speaks of people coming up to him and saying how his character inspired them to go into business and finance.

5. Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father (2006)

The great thing about this little known documentary is how centered it is on individuals and how they react when the actions of the Canadian government change their lives dramatically. When Andrew Bagby, a physician in Latrobe, Pennsylvania is murdered, his childhood friend, filmmaker Kurt Kuenne, sets out to make a tribute film to his memory for his family and friends. As the police investigation reveals that his ex-girlfriend Shirley Turner might be responsible for his death, she flees to Canada, where she finds out that she’s pregnant with Andrew’s child. The remainder of the film has Andrew’s parents moving to Newfoundland in an attempt to gain custody of their grandson while they wait for the lengthy Canadian extradition process to take place. The events of the film have resulted in a serious attempt at bail reform for those convicted of murder, as well as changes to the Canadian child care system. It’s the most powerful and well-edited documentary I’ve ever seen.

4. JFK (1991)

Oliver Stone’s third (first?) entry on this list is also his best film. It tells what Stone refers to as a “counter-myth” to what he considers the myth of the Warren Commission, that is, the commission appointed to investigate the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, which found that he had been killed by a lone assassin. Stone’s film rips through the many flaws of that investigation and presents an amalgam of the ideas that support a conspiracy to kill the president. Kevin Costner stars as New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, whose investigation of the murder puts him and everyone he knows at risk, and yields the belief that certain forces in the military-industrial complex may have opposed Kennedy’s policies regarding Vietnam. The film was extraordinarily controversial when it first came out, having essentially spat in the face of official U.S. history. After showing the film to Congress, they agreed to declassify dozens of documents pertaining to the assassination. Stone dedicates JFK to “... the youth, in whose spirit the search for truth marches on.” When pressed by a reporter about whether his investigation may be damaging the reputation of the United States government, Garrison responds with, “Is a government worth preserving when it lies to the people? Let justice be done though the heavens fall.” A stunning film that refuses to let the conspicuously suspicious nature of the assassination be glossed over by a shoddy investigation, JFK reminds us that we have a responsibility to ourselves and to history to find out just exactly what happened to our 35th president.

3. Boys Don’t Cry (1999)

The film that gave Hilary Swank her career is the emotionally exhausting tale of Brandon Teena, born Teena Brandon, a girl who more closely aligns with the male side of the spectrum, such that she dresses like a boy, cuts her hair like a boy, and essentially becomes one minus the actual surgery. The story takes place in Nebraska, where Brandon meets and falls in love with Lana (Chloe Sevigny) and befriends her male pals John and Tom. (Spoilers ahead) Though Lana’s love for Brandon doesn’t waver in light of the truth about her sex, when John and Tom find out they rape and kill Brandon. As disturbing as the film is by itself, it’s significance was made even more poignant when it came out by the infamous murder of Matthew Shepard in Wyoming. The event and film sparked national debate about sexual orientation hate crimes, and the film itself is so disturbing I’ve only been able to watch it once.

2. All The President’s Men (1976)

Alan Pakula’s film is a fascinating look into how two journalists assigned to an initially benign story uncover the massive coverup behind Watergate. Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman play Bob Woodward and Carl Burnstein, who find themselves in a situation stranger than fiction as this story they’ve been assigned to cover turns into the scandal of the century. Aided by their editor and an anonymous high-up government official code-named “Deep Throat,” (snicker) these two face an affront to both their personal and professional lives by pursing the story, but nonetheless, they keep digging. A fantastic David versus Goliath story, All The President’s Men shows us the little guys do in fact keep the big ones in check. This film (and the true event) inspired leagues of aspiring reporters.

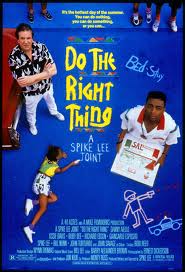

1. Do The Right Thing (1989)

Spike Lee’s third feature film examines racism by allowing us to visit a New York City neighborhood and follow the events of a hot summer day. It’s a melting pot of races. You’ve got the Italians in the pizzeria, the Asians that own a convenience store, the old black men that drink beer and shoot the shit on their corner, and the white cops, whose least favorite place to visit is this particular neighborhood. Lee plays Mookie, a delivery boy for the aforementioned pizza parlor, through whose eyes we see the events of the day unfold. The film shies away from optimistic, “can’t we all just get along” philosophies, instead advocating two seemingly contradictory paths at the end, each by Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, respectively. “Violence is never justified under any circumstances,” and “violence is not violence, but rather intelligence when used in self-defense.” Mookie’s actions in the end of the film would appear to lean towards the latter of the two statements, and his careful reconciliation with his boss Sal, (the Italian who owns the pizzeria) comes only after such “intelligence” is executed. Sometimes, peace only comes through outrage.

Honorable Mentions: American History X, Minority Report, Wag the Dog, Inherit the Wind, M*A*S*H*