It’s rather redundant at this point to observe that Quentin Tarantino likes genre films. The director’s entire career has been built on his unique talent for pastiche, mixing and matching elements of kung fu, blaxploitation, grindhouse and gangster flicks into his fiercely energetic, violently bonkers creations. With Django Unchained, the auteur of homage has now set his sights on the Western.

Not that Tarantino hasn’t incorporated Western tropes and styles into his films before – both Kill Bill and Inglourious Basterds conspicuously referenced Italian spaghetti Westerns – but this is certainly the first time he’s tackled the genre so directly. Odds are the film will be chock full of references to Tarantino’s favorites, so here I present a guide to some of the classic Westerns that have influenced QT’s style so that you too can play a game of film history “I Spy” at the theater this week.

THE ESSENTIALS

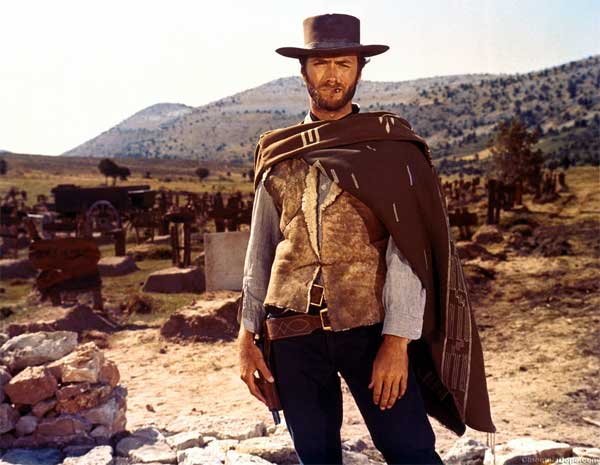

Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name Trilogy - A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), The Good The Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Leone’s three films with Clint Eastwood as a roaming bounty hunter (alternately called Joe, Manco or Blondie depending on the film) are rightly seen as the pinnacle of the Spaghetti Western sub-genre. Filmed in the barren wilds of Spain and Italy, Leone’s films presented a grittier, more amoral vision of the American West than had ever been seen before.

The Mexican standoff between Eastwood, Eli Wallach and Lee Van Cleef at the end of The Good The Bad and the Ugly is a virtuoso piece of filmmaking, and Tarantino has borrowed that scene’s suspense (though generally on a much less operatic scale) in several of his films.

The Wild Bunch (1969)

Before Quentin Tarantino, there was Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah pushed the bounds of “acceptable” mainstream cinema by jamming his films with harsh, exploitative violence, and remains a controversial director to this day – exactly the kind of guy that Tarantino reveres. The Wild Bunch follows a gang of outlaws who become entangled in the Mexican Revolution, staunch representatives of the dying West, which is quickly being overwhelmed by the advance of modernization.

The film’s climactic “Battle of Bloody Porch” sequence is a clinic of excess, a symphony of gunshots and exploding squibs that very much looks like what Tarantino would’ve been doing 40 years ago.

Django (1966)

There’s that great moment in the trailers for Django Unchained where Jamie Foxx’s protagonist spells out his name to a fellow bar patron: “The ‘D’ is silent.” But I wonder how many casual viewers get the real joke there – namely, that the other patron is none other than Franco Nero, the lead actor of the film whose title Tarantino has cribbed

Sergio Corbucci was second only to Leone in influence when it came to Spaghetti Westerns, and his best film ups the ante from the Man with No Name Trilogy by drastically increasing the violence and presenting a more conflicted hero, torn between money and revenge. Django follows a mysterious gunfighter (who constantly drags a wooden coffin behind him) looking to avenge his wife’s murder. Perhaps not the same kind of matrimonial conflict at the heart of Django Unchained, but not far off the mark either.

DEEP CUTS

Rio Bravo (1959)

Dedicated Tarantino enthusiasts will know that the director actually lists Rio Bravo as his favorite film of all time. He loves the film so much he even uses it as a romantic screener: “When I’m getting serious about a girl, I show her Rio Bravo and she better $@#&*%! like it.”

This classic Howard Hawks/John Wayne collaboration was supposedly made as a response to the anti-McCarthyism of High Noon, as John Wayne’s sheriff enlists the help of a cripple, a drunk and a young gunfighter to hold the brother of a notorious outlaw in jail. Tarantino is on record as enjoying the “hangout” quality of Rio Bravo – the time Hawks spends just letting his characters talk, allowing the audience to get to know them and care about them through their personal tics of dialogue. That’s certainly relatable to QT’s canon.

I Shot Jesse James (1949) and Forty Guns (1957)

Before Tarantino there was Peckinpah, and before Peckinpah there was Sam Fuller. A master of low-budget genre flicks with controversial themes, Fuller started out writing pulp novels before becoming a terrorizing, gun-toting director. His two Westerns are incredibly tame by today’s standards (and don’t share Tarantino’s flair for dialogue), but at the time, Fuller was a shocker and his influence on QT is still obvious.

I Shot Jesse James, for instance, is notable for its predilection toward intense, emotional close-ups. Overall the film’s a bit of a dud, but there’s at least one exceptional scene where the “traitor” Robert Ford confronts a bar musician playing the famed, emasculating song “Jesse James.” It’s got all the suspense of the bar scene in Inglourious Basterds, though it lasts only a fraction of the time.

Forty Guns, meanwhile, treats amoral gun violence with a frankness unseen by most studio Westerns. It’s the kind of boundary-pushing, borderline-of-good-taste film that Tarantino hopes Django Unchained will be.